Having traveled over 3000 miles in their migration, they arrive in the mountains southwest of Mexico City, east of the hillside town of Angangueo. This time of the Winter, the nights are long and temperatures can drop below freezing. They huddle together for warmth, remaining still until dawn. An hour or so after the sun begins to warm the air, you can see their first stirrings; Tentative evaluations to confirm that they’ve survived the night. As the warmth begins to penetrate their bodies, they shift and twitch to circulate the blood, their movements gradually becoming more purposeful. At last, they burst forth from the comfort and security that had ensconced them through the night, emerging to greet the day, it reveling as much in their beauty as they do in its. They usually make coffee and oatmeal right after. And today was a big day; they were going to the Monarch Butterfly Sanctuary.

After driving south out of Guanajuato state and briefly through Queretaro and the State of Mexico (but, of course, I don’t have to name all the Mexican states for you! Right?), we reentered the much-feared Michoacán. At the border, no more than an overpass with a welcome message similar to what you’d see in the US, there was definitely an increased security presence, a few police cars and trucks with heavily armed men, but as usual, they didn’t give us a second look. And more importantly, they didn’t flag us down and say “Dios mio! What the hell are you doing entering Michoacan?!” So that was good.

Graffiti in the towns we drove through reflected the fact that some locals either thought that the contributions the cartels made to the communities were positive, a common and quite ingenious insurgent strategy, or that living with them was preferable to the violence of fighting them. They said things like “END THE WAR ON THE CARTELS” "or “MR. PRESIDENTE, NO VIOLENCE IN MICHOACAN.” It’s also possible that the brother-in-law of the cartel leader went to the ferreteria and bought a can of spray paint, a less common but equally ingenious strategy.

Small curvy lines shown in yellow on the Guia Roji, the road atlas sold at any of the OXXO stores usually attached to the state run Pemex gas stations, are the local, free routes which wound us down from double red-lined toll roads into Angangeuo, the gateway to the butterfly sanctuaries. Actually, “cascaded” might be a better word since the town sat on either side of a river in a steep narrow valley that had clearly been a wall to wall waterfall a few months earlier. With every other bridge back and forth across the river washed out, we picked our way through the side streets, at one point asking directions from a truck full of 30 Mexican army troops who looked as startled to see us as we did to see them.

The 10km road to the El Rosario Monarch Mariposa Sanctuary had been all dirt until it was recently cobbled to accommodate the hoards of Mexican tourists who descend on the area in the high season from Jan – Feb. Because you know the slogan: “When you think of long range driving comfort, think cobblestones.” It’s better than their previous two: “Cobblestones, the first name in filling removal.” and “Rupturing spleens since 400 BC.”

But we were early in the season and though the Hotel Givali, three quarters of the way up the road, boasted a hundred vacant rooms, a rockclimbing wall, children’s playground and farm animals, all laid out in a quaint, park-like setting, we settled in beside a palapa in the camping area at the back. We were entertained as the spritely female proprietor would disappear each time we asked a question and then reappear with the answer just as we decided she’d forgotten about us. We cooked up some chicken and the wilting broccoli that had been in the fridge since the market in Patzcuaro, shifted the back seats into “living room mode” and crawled inside to get out of the cold.

Our palapa at the Hotel Givali. Ann in her capacity as roof top tent setter-upper and tearer-downer. The secure gates of the hotel are usually locked so ring the bell or knock loudly.

Our plan had been to go to one of the newer and less popular butterfly sites, having been cautioned by the Lonely Planet that El Rosario can receive 8,000 visitors a day, but as we pulled into the terraced parking lots, there was not one car. We finally noticed a raised roof van, the type favored by German overlanders, pretty much the only other nationality besides Canadians we’d been seeing on the road, parked off in a corner. The utilitarian diesel vans, all painted either a matt light blue or tan and with the distinctive European plates, elongated white rectangles with black lettering, are commonly shipped over to Canada for a drive around the Americas. Like most of the Germans we’ve talked to, these folks were very nice, with some English, and seemed surprisingly fearless about setting off into unknown parts halfway across the planet from the Black Forest. Another guy we talked to had been sleeping in his van behind Pemex stations and had just driven the road that shadows the Mexico-Guatemala border through mountains known to be used by the remaining Zapatista rebels and human traffickers smuggling Central American immigrants across the border into Mexico. These Germans have gewerstemeiners the size of schlosses! (don’t bother translating that) Then again, we’re on a bad-ass trip as well. I mean, to a lot of people, what we’re doing is pretty hard core.

Now where was I? Oh yes, the butterflies.

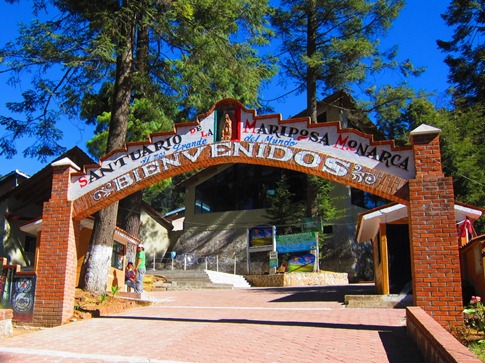

The path to the gate of the sanctuary wound through a ghost town of at least a thousand deserted stalls sided with old scraps of wood that people on green renovation shows on cable would pay a fortune for and presumably filled with local crafts and butterfly souvenirs during the high season. But thankfully, first thing on a Monday morning in December, the only person around was a charismatic woman with a huge smile on her face who had walked down to where we’d parked and, politely but proactively, told us in Spanish that should we need anything to eat or drink before heading up the hill, she’d be waiting for us. When we approached her stall, she rattled off a list of 10 different dishes and preparations, pulling back cloths to reveal raw meat in bowls on the table beside her wood stove. We made our apologies, explaining that we’d brought food in our pack but figured the least we could do was have a cup of coffee. It was then, sitting on the bench at one of her long tables lined with Boing! fruit drinks in tall multicolor bottles that we realized why we liked her so much; She had the same smile and eyes as our friend Kathleen from home!

She got a big kick out of it and when we took a picture, she said she wanted a copy. In the most culturally and socio-economically sensitive way we could manage with our intermediate Spanish (which is to say… not), we asked her if we could email it to her. She thought that was pretty funny and explained that we’d just have to come back and bring it to her.

At the entrance, a few young men hung around, sitting on the turnstiles. We’d heard that all the guides at the sanctuaries were volunteers who worked for tips, and as we approached, one of the guys jumped up, it obviously being his turn for clients. In addition to not speaking English, our guide was a certified “soft talker.” The closer you leaned in to hear him, the softer his voice would get until you suspected he was now talking to the butterflies, informing them that we were on our way. After gathering that it would be over an hour walk or 30 minutes by horse up to where the butterflies were, we negotiated about $5 each for horses. Though the logic of the time estimates broke down when the two horse tenders and our guide walked along beside our horses carrying on animated conversations and yet somehow managed to get there at the same time we did, at 10,000 ft, we were glad to have hitched a ride up the steep, loose path.

After about 20 minutes, we dismounted and walked another 10 until butterflies started to appear, three of four of them flittering around in the beams of sunlight in front of us. And when we got to rope across our path, we looked up into the trees and realized that they were literally dripping with them; Clusters of butterflies two feet thick and four feet long dangling from branches like giant pine cones, the gray undersides of their wings acting as camouflage until they were ready to take flight in a vivid orange flash.

As the sun shifted, they would slowly come to life like a robotic army being summoned by its evil creator, testing their hydraulics and downloading instructions. With all systems go, they’d peel off, momentarily adjusting their trajectories as they broke free of the gravitational pull of the mothership and calibrated their flight plans. At least it’s easier thinking of them that way than trying to explain how 8 months prior, a mass of butterflies had left these mountains headed for the Great Lakes in the northern United States. Before reaching their destination, they would have reproduced and died two times, with each subsequent generation continuing on the prescribed course. In the Fall, these great grandchildren would have turned south and reversed the migration, again reproducing and dying twice along the way before they arrived en masse, four generations later to the same mountains. Yeah, I’ll stick with flying robot warriors.

Above are just some of the pictures of the incredible day. I’ve learned my lesson about cultural and socio-economic sensitivity so I won’t presume you have an email address where I could send more, but we could bring some extras if you wanted to meet us back at the sanctuary. We’re trying to coordinate a time to meet up with our Kathleen doppelganger; I poked her on Facebook but she hasn’t responded yet.

I also put together a little video I hope will give you some of the experience of being there.

That night, we ended up in Valle de Bravo, though it took us a while to be sure of that. We tried to find the campground where we’d read in San Miguel that Kevin and Ruth had been staying. We knew that the campground was called “Embarcadero” something and was also a boat ramp, so we drove into an unmarked gate towards the lake and some stored boats. We asked the first guy we saw if this was the “Embarcadero.” He kinda looked around at the boats behind him, shrugged and nodded. About then our Spanish kicked in and we realized that “embarcadero,” a word we frequently hear living in San Francisco, just means “pier” or “wharf,” thus making our question a pretty dumb one. We didn’t recognize the area from Kevin and Ruth’s blog, so we decided to head into town to find a hotel. We’d later find out that around that time, Kevin and Ruth checked our SPOT tracker and saw that we were about 100 yards from them. They came running over but we’d just driven out.

That brings us to the next problem. We were driving along the shores of Lake Avándaro, often compared to the Italian lakes, but we couldn’t really tell whether there was actually a town called “Valle de Bravo” or if that was just the name of the area. Had it been the intersection we first came to up and away from the lake? Was it the crowded and dumpy mainstreet we’d been funneled down? Or could it be over near that old church we’d glimpsed down a side street? The imprecise maps we had loaded on the GPS of course were no help so, we continued on the road, assuming we’d see a sign for the centro or hotels. Before long were at the south end of the lake, so we turned around and started back. Somehow, trying to retrace our route dead-ended us right into a nice zocalo we’d never seen before. We noticed a sign on the church announcing that there was free wifi in the square so, in one of the weirder moments of the trip, we got out the laptop, got online and checked our own SPOT tracker to find out where we were. We then plugged the coordinates into Google Maps and searched for hotels nearby. With several results shown, we switched to “Street View” and started walking around looking for them.

A day with millions of butterflies, a lake fit for Jorge Clooney and public wifi in front of a centuries-old church. I think I need to get in touch with the Mexico tourism office.