I had gotten myself too psyched up the night before about the horrendous traffic, crooked cops and misleading signage we should expect driving anywhere near Mexico City. Still, I was unwilling to take the long, circuitous detour suggested by the Church & Church book, despite their assurances that no one had ever reported that another route was worth the effort. Never mind the cryptic “Hoy No Circula” rules attempting to reduce congestion by prohibiting cars with license plates ending in certain numbers from driving on set days; No one could really even confirm that these applied to foreigners, instead suggesting that corrupt Mexico City cops were going to pull you over no matter what you did.

After leaving Valle de Bravo early, we decided that a dirty, long range truck looked like more of a target than a shiny one. After a stop at an “auto lavado,” just a vinyl shade on a metal frame, a pressure washer, a tank of water and two guys who proceeded to scramble around the truck for 25 minutes scrubbing 6 weeks of bugs off the front of the roof tent and from inside the grill for 25 pesos, we headed towards Mexico City with every nook and cranny of the truck securely padlocked, 200 pesos of bribe money in my wallet, and expecting the worst. Of course, this is usually a recipe for having your expectations met.

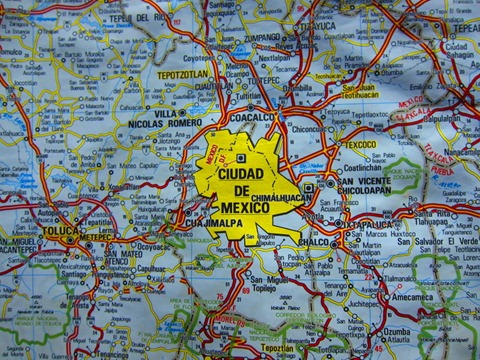

As with everything, the reality was somewhere in between. Yes, we got stuck in frustrating traffic on roads with no semblance of lanes marked by signs that led us towards a destination for a period and then bafflingly just disappeared or pointed in two opposite directions to the same place or refused to use any of the names of what seemed like major areas on our maps. Since none of the numbered highways we saw corresponded in any way with the roads on our maps, we just pretended the blue “snail trail” that records our route on the GPS was an “Etch-a-Sketch” and tried to draw the route we’d pictured on the tiny screen. Of course, any time our eyes were off the road, we’d hit a pothole that would shake the dash so hard we feared it would erase our trail just like on the low-tech alternative.

These bus drivers know how to cut it to within inches. Only three on a motorcycle? Who’s taking care of the baby? I knew VW Bugs were underpowered but… Smog where Mexico City should be.

When we finally pulled through the chain link fence and into one of the grassy sites at the Teotihuacan Trailer Park, we’d been on the road for about 6 hours but had maintained good spirits. He walked over about 15 minutes after we’d arrived, as we were popping the tent, putting out our chairs and fixing some lunch, and lingered just outside our periphery. We sat down with ham and cheese sandwiches, unsure whether to offer him something; it was clear that’s what he wanted. Then, right on cue, came the pity cough. At first just a stifled throat clearing as if to say, “Oh, excuse me, I just seem to have a little something caught in my throat,” but it escalated until he wretched out one of those coughs that only seem possible after years of smoking and that you’re sure will produce a small section of lung. I half expected to hear the words, “Be a dear and get Nana a Chivas and soda.” It was the cough you associate with the Plague or some other epidemic capable of wiping out villages and countrysides, serfdoms even.

Although in his case, we suspected heartworm, and though the conversation would often turn to whether he could be trained and how nice his white coat would look after a bath, we had to keep reminding ourselves that he belonged to the owners of the campground and was not our dog. Still, “Café con Leche,” the name we gave him because he was “coughy and white,” would lie by our feet in the mornings, waiting for crumbs of the latest 5 peso treasure from the panaderia, as we thumbed through guide books and planned the day. Of course, he was equally happy if he got a better offer.

Teotihuacan was the first of two archeological sites we’d be told was the model for planned urban development in early Mexican civilization. The second would be Mont Alban outside of Oaxaca, and we began to think of that claim a little like the signs for “World’s Best Pie” outside the truck stop diners we’d seen a month before in Bakersfield.

The next morning, we flagged down a colectivo which would take us out of the town of Teotihuacan and to the pyramids which are actually located in San Martin; This was the first questionable move by the supposed master planners. Then, perhaps in honor of those pre-literate designers, a complete lack of signs meant we had to rely on a guy on our bus who was old enough to have been a Junior Sacrifice Technician in the original city to tell us when to get off for the pyramids.

We spotted a pyramid visible in the distance beyond the mirage of a guard house, down a crushed lava rock path flanked with food vendors making sure we knew there was nothing to eat inside. Except for rows of aloe and a few trees on either side of the path, the site was exposed to the full force of the Mexican sun, and we again questioned the wisdom of planning a development in the middle of this wide open, flat land (apologies to anyone from Texas). As we strolled through the gate towards the massive tour busses from Mexico City the guards were used to receiving, they seemed a bit confused as to where exactly we’d come from; We didn’t have a much better idea. We headed directly for the Pyramid of the Sun for the requisite “look how steep these stairs are!” pictures while other tourists took “look how sweaty and out of breath that gringo is” shots.

We descended into a sea of hawkers selling all manner of cheap jewelry and tiny carved pyramids which we were assured were “casi libre” (almost free). After conspicuously changing course and avoiding eye contact with the seventeenth guy trying to sell us a “jaguar whistle” that sounded something like Café con Leche trying to play the recorder, it wasn’t hard imagine the justification for human sacrifice on the Calzada de los Muertos.

Despite the paved central road necessary to accommodate the hoards of school children dressed in the matching sweat suits that seem to be the standard for school uniforms and tourists making the trip from Mexico City, the ancient city, established sometime around 200 BC and occupied, at times by up to 200,000 people, for almost 1000 years, is a powerful site to visit. It’s possible to imagine the massive Pyramids of the Sun and Moon, sheathed with smooth red plaster that has since been worn away to reveal the cobbled skeleton below, cutting an impressive figure on the horizon and striking fear into approaching enemies; That is, if the asthmatic jaguars whistling at them hadn’t already.

We ducked behind one of the stone walls, the grout speckled like the rest of the complex with tiny lava rocks, and snuck a snack of fresh tortillas and cheese out of the pack while I shot a couple videos I’d later compile into time lapses I think capture our experience. Check it out below.

That evening, we did a thorough lap of the town of Teotihuacan on a mission to find tamales. When we found the building where I remembered seeing the word “Tamale” painted in red block letters on a white wall, we got a workout on the conjugation of the verb “hacer,” to make.

“Hace tamales?” Do you make tamales?

”Tenemos todo para hacerlos.” We have everything to make them.

“Tiene tamales hechos?” "Do you have tamales made?

”No? Puede hacer algos para nosotros?” Can you make some for us?

“Sabe donde los hacen?” Do you know where they make them?”

They suggested heading to the centro, so we did an exhaustive search of the mercado and the stalls set up in the central square selling Christmas decorations. We finally found them on the last row and thoroughly entertained the lady and two customers sitting at a child size plastic table and chairs in her stall with our questions and confusions about what exactly was in each type she had. We ended up with two rojos, a verde and another we never got the name of, and all were delicious.

The Lonely Planet explains how to get from Mexico City to Teotihuacan so we knew only that it could be done and that the last bus left Teotihuacan at 6 pm. We planned to meet “TommyD,” a guy with whom I’d exchanged some posts about the security situation in Mexico on the Expedition Portal forum (see San Miguel de Allende post), who lived in Mexico City and offered to meet up with us at 1:00 in his neighborhood of Coyoacan. “Let's meet at the coyote statue. Can't miss it - right in the centro.” This last statement reminded us that he doesn’t know us very well.

With no idea where to catch the bus in Teotihuacan, we walked into town and asked a cop who directed us to a line of people waiting under a shelter. As we looked around for a ticket window, a woman started working her way up the line selling the 26 peso (just over $2) tickets for the hour long ride. After a cursory but somehow confidence inspiring pat down, we took two comfortable seats on the modern looking bus that pulled up 5 minutes later; though it sounded a little less modern each time the driver was unable to get it into second gear and, after what would seem like 30 seconds of crunching and grinding, would just go straight into third.

Outside the window, in the largest city in Mexico and the third most populous metropolitan area in the world, encampments covered with tarps or sheets of rotting plywood were sandwiched between the lanes of the highway. While throughout Mexico, we’d seen people living in tough conditions, they often had a sense of contentment about them; They obviously had hardships but, for the most part, they also had a goat or a donkey and a house with four cement walls and a solid roof and were making it work. We’d also heard stories of farmers selling off portions of their land to developers and, rather than using the money to add a room or build an attached bathroom, being content enough with their lifestyles to buy Hummers instead. But these tight quarters and sanitation conditions were a completely different story, and we immediately started thinking about looking for charities working in the area.

Up on the hills, unpainted cinderblock houses were tightly packed into a grayscale version of Guanajuato. I found myself wondering how much of the peaceful quality of life we’d perceived in Guanajuato had been just a fresh coat of paint and how the UNESCO designation had affected the aesthetics of the city. What was the relationship between a clean, bright coat of paint and the mood and ambitions of those inside? Did one affect the other and vice versa? Or how would it affect interest from those outside in helping them? Clearly, paint is not the answer to poverty but could represent and encourage a hopefulness that would have a positive effect. Then again, I can’t help but think of the logo for a paint company we see everywhere in San Francisco that shows a drawing of the Earth with a paint can dumped over the top of it and the words “Cover the Earth.” I have no idea how they think that looks like a positive thing.

When the bus pulled into a congested area with several other buses, a group of people got up to get off, so we did the same. Out of sheer luck, we found ourselves at an entrance to the underground Metro system which, other than feeling a little outdated, like it might have been a hand-me-down from the 1970’s Chicago bought at a subway thrift store, and the line of 40 people waiting for a single token window with not an automated machine to be found, was clean and functional. Even luckier, we were at the Indios Verdes station on the same “sage green” line, not to be confused with what seemed like at least two other shades of green, that would take us all the way to the southern part of the city to the Coyoacan station.

Our luck ended when we emerged from underground and into a small plaza where no one seemed to know anything about a “statue of a coyote that couldn’t be missed.” We mounted brief explorations in each direction, into an office park and a large modern mall, asking people if they knew where the statue was, each time honing and perfecting our Spanish question-asking skills until I thought we were getting quite good at it. The last cop we asked seemed to agree, though unfortunately, his answer was like the rest: that there was no statue of a coyote nearby. But then he added, “Solo en el Centro.” We told him we didn’t want to go to the center of Mexico City and had been told this statue was in Coyoacan. “Si, el Centro de Coyoacan.” He proceeded to explain that we could grab any colectivo labeled Coyoacan Centro and ride it 15 minutes in the opposite direction we’d been walking to get there.

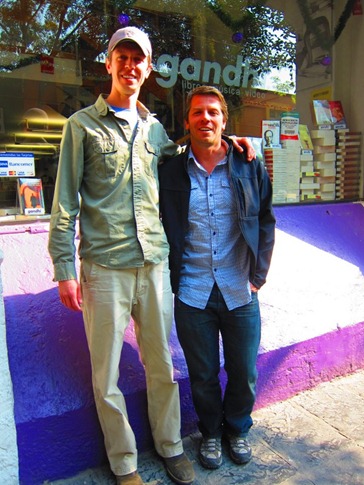

It was 12:59 pm, two hours after we’d left the campground in Teotihuacan and one minute before our scheduled rendezvous, when we walked through the zocalo towards the prominent coyote statue and found Tom just as he’d described himself: “the tall gringo,” and that was when he was sitting down.

The three of us had a nice lunch and a couple Micheladas, beer poured over a shot of lime juice in a glass, best with a dark beer like a Bohemia Obscura or a Negra Modelo in my opinion. Tom ordered a Cubano which adds a spicy tomato sauce like a Bloody Mary, and in some areas of Mexico, is what you get when you order a Michelada. Best to ask at a restaurant if theirs is “picante” or “solo con limon.”

Conversation ranged from Tom’s field work around Mexico towards a PhD in Biology to his wife currently living in Florida and visiting when she can to our trip on the whole, only briefly touching on security in Mexico, which we’d all agreed was just a matter of common sense, awareness of one’s surroundings, and an acknowledgement of some degree of elevated risk. We parted with the usual “if you’re ever in San Francisco’s” but in this case, with a true hope that we see Tom again and get to hang out some more.

We walked around Coyoacan a little, exploring an “artesenal market” but finding that they were all starting to look the same, before stumbling on the Frida Kahlo museum in the house where she had lived with Diego Rivera (sadly, no relation to Jeraldo or Dora). The location in their home, including a bed equipped with an easel suspended above it so Frida could paint while in traction following a bad accident at age 18 and his quotations scattered throughout their garden, combined with the juxtaposition of her artwork and his photography, created a vivid picture of two exceptional people in a loving and supportive relationship during a transitional time in Mexican cultural history. The fact that we spent a month in France this summer without setting foot in a single museum should tell you that it’s not to be taken lightly that we we recommend checking this one out if you’re ever in Mexico City.

Feeling like it was getting late, we started looking for a colectivo back to the Coyoacan Metro. Now masters of the Mexico City transportation system, we got on one headed for another station figuring we could transfer lines if we needed to. We started to exchange glances when 20 minutes later, we had rolled out of the relatively posh Coyoacan and into what looked like “less desirable” neighborhoods, so we got off at a busy intersection with overflowing produce stands on all four corners. We started walking, once again refining our question-asking skills every few blocks, though we couldn’t help but sense an increasing resemblance to a cautionary tale in the Lonely Planet by the second.

At one point, we could sense a change in the flow of pedestrian traffic; People walking away from the intersection ahead had a certain elevated purpose to their gait. I recognized it from being near the 16th and Mission BART station in San Francisco around 6 o’clock on a weeknight where everyone’s on their way home from work, glad to have been released from a metal tube beneath the earth, hungry and moving in a sort of run-walk. We swam upstream the rest of the way to the Universidad station and landed a solid inquiry with some college students that confirmed we could take this line all the way north and be at the Central del Norte bus terminal with one line change.

Now aware that time was getting tight but unwilling to actually do the math that would tell us that for the last bus to leave Teotihuacan at 6:00 pm it would have to have left Mexico City by 5:00 pm, 15 minutes ago, and counting on some underground time change but also starting to run scenarios that involved hotels in Mexico City, we made the transfer to the yellow line. As we sat down on the train to ride the one stop to the bus terminal, we looked up at the system map mixed in with the ads for English schools and vocational training that seem to occupy this space in all subway systems all over the world and saw a list of unfamiliar stop names laid out along an orange line. Orange line?! This is supposed to the yellow line! Nevermind, we thought, as we pulled into the Central del Norte station; They had just put an orange line car on the yellow line. Good one, fellas.

Just a couple more questions were going to do it for us. The first one resulted in us being pointed to the far end of the large bus station, laid out like an airline terminal with counters for each carrier and a list of destinations behind them, where we were told the bus to Teotihuacan boarded. One down. Our final question was kind of a crucial one: When does the next bus to Teotihuacan leave? He let loose on his computer with one of those keyboard flurries only ticketing agents are capable of, looked up and calmly said “One minute.” We grabbed out tickets and dashed out the door and onto the bus, not quite sure how we’d made the last bus from Mexico City to Teotihuacan and hour after it should have departed.

That night, we indulged in one of our new found favorites: pollos asados, rotisserie chicken on spits or pressed into wire baskets turning slowly over a wood fire in anything from a makeshift cinderblock box to a domed oven with an intricate basket-weave of brick. Like at home, there can be a wide quality difference between them, but standing behind the truck back in the Teotihuacan Trailer Park, hunched over the dropdown stainless steel table, tearing the moist meat off the bones after a long day of uncertainty and public transportation, we felt like we’d avoided the Safeway chicken and found the Whole Foods.

We packed up the next morning and, this time, successfully skirted Mexico City, our next goal being Oaxaca (wa-ha-ca) and the hope of finding an apartment where we could spend Christmas. The long stretch between Mexico City and Oaxaca appears as a blank spot in most guidebooks with some mention of stops in the capital city of Puebla, climbs of the Pico de Orizaba volcano, or side trips out to Vera Cruz on the Gulf Coast, but we were ready to be moving south, so we split the drive into two days with a stop in Tehuacan. From what I can find, the similar root of the ancient city we visited a few days before and this one is the Zapotec word Teokan meaning “island of learning.”

Despite a rating as no more than a stopover in the Lonely Planet, we really enjoyed this small but modern Mexican city. In fact, we got the front brake pads (balatas) changed at a spic and span Pirelli Tire dealership and, even after they had to send a guy all over town on a bike to find our pads, flushed and replaced the brake fluid and did a good cleaning, only paid about $80. The original estimate was only $20 more and they were going to machine (rectifica) the rotors but backed off when it was clear I knew they didn’t need it; Not a scam unique to Mexico. The only problem with the accommodations was that when we looked at the credit card statement a week later, it took me a while to explain to Ann that the $45 charge to “HOT MEXICO” was in fact for The Hotel Mexico. She bought it.

That night in the zocalo, we noticed a business venture we remembered seeing in Guadalajara: a guy with a fleet of child size, electric play vehicles for rent. As we sat at a nice outdoor café enjoying a plate of arrachera, a piece of flank steak marinated to within an inch of its life, we watched couples stroll along the poinsettia-lined paths of the zocalo, hand in hand with one child leading the way on a miniature plastic ATV and another bringing up the rear in Barbie’s hot pink Dream Jeep.