As soon as you cross the border into Guatemala, you feel a distinct change. Dark green hillsides, planted with what might be coffee beans, provide a background for the trees blooming with small pink flowers that line the road; unpaved sections and killer potholes lurk, waiting for you to become complacent behind the wheel; and houses are once again the concrete and rebar we’d seen throughout Mexico.

At first impression, Guatemalan faces are a little more stern. From gas station attendants to kids pushing bicycles down the side of the road, there’s a certain darkness in the eyes that followed us as we drove by. It’s not likely that each one was thinking about the fact since the 1920’s, ownership of up to half of Guatemala’s agricultural land has been in the hands of US corporations who, when threatened with redistribution in the 1950’s, lobbied the US government to end what Guatemalans refer to as the “10 years of Spring” by fomenting (thanks, Stevie) a coup and installing 30 years of sympathetic dictators backed by a US-trained and funded military who would go on to form death squads that would “disappear” 60,000 people before 1980. But then we remembered a comment someone made to us in Baja that a smile and wave will often be greeted in kind. So, we sped through the Guatemalan countryside toward Tikal, smiling and waving to everyone as we passed, whispering under our breaths, “Sorry, ‘bout that everyone. That’s our bad.”

The towns surrounding the ruins at Tikal are an easy drive from the border, and we pulled into El Remate at the eastern tip of Lago de Peten Itza in the early afternoon. Most tourists stay in Flores, a town that fills a small island in the southwestern corner of the lake, about an hour away or camp at the ruins. Having heard that Flores is crowded with tour buses and that, while the tent camping is in a nice grassy field with palapas, vehicle camping is limited to the parking lot, we cruised the dirt road north of the lake in and grabbed a cabana at the Hotel Mon Ami.

Before we even set foot in the room, we were back in the truck and heading the 30 km up the road to the ruins. Still feeling like ruins had been ruined for us in the Yucatan – or rather just overdone – we figured we’d cruise up there and just quickly tick Tikal off the list. At a checkpoint, we gleaned from a barrage of Spanish that we were being given a slip of paper with the time on it. We were to drive no more than 45 km/hr through the next section of road. If we arrived at the other end in anything less than 20 minutes, we’d be given a speeding ticket. An interesting challenge calculating how much under 45 we’d have to go for how long after realizing we’d been going 50 or how much over 45 we could go if we’d been going slower. It reminded me of reading Bumfuzzle’s experiences in “The Great Race” where teams in vintage cars “raced” across the country, on each leg trying to arrive as close as possible to predetermined “perfect time.”

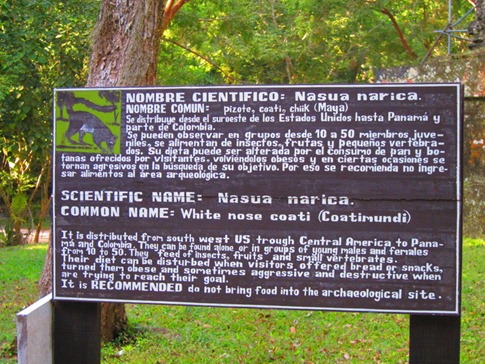

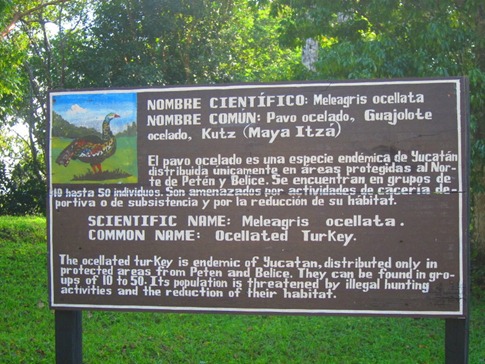

The reason for the speed control was in the yellow, diamond-shaped signs every kilometer or so showing a black outline of a different animal. According to the signs, we could expect to slam on the brakes at any moment to avoid hitting a crossing jaguar, snake, turkey or coatimundi (think anteater/racoon/lemur threeway). In fact, the only one we saw was an Ocelated Turkey which looked much more like a peacock than the Thanksgiving butterball its outline had made it out to be.

“Borrowed” picture of a coatimundi.

The wide path, built to accommodate the throng of tourists delivered each morning by the tour buses, was empty as we paid for our tickets and walked through the gate at around 3:00. In fact, the guard told us he’d stamped our tickets for the following day so we could come back again the next morning if we wanted. Passing a huge ceiba tree, the national tree of Guatemala and symbol of the connection between the heavens, earth and underworld to the Maya, we climbed steps through the thickening jungle as we followed signs for the “Gran Plaza.” It sounded like if we’d been there, we could say we’d done that.

The history of Tikal follows a course familiar to other ruins with its primary development and occupation in the 1st century AD. Though we’d come the long way through the Yucatan and Belize, as the crow flies, Palenque is quite close to the north, over the Mexican border. The Gran Plaza is an open square framed by two large pyramids and buildings that look like temples or houses. Ocelated turkeys roam the grass like prehistoric guardians of the ruins. A wooden stairway, frighteningly steep and with treads spaced to easily allow a small child to fall through, leads up the side of one pyramid allowing for a great view of the other and the jungle beyond.

Having spotted another large pyramid on our climb and hearing the sounds of howler monkeys in the trees, we continued deeper along the paths snaking through the site, finding ourselves increasingly drawn in. They’ve done a great job, despite receiving a huge number of visitors, to make the site feels very natural and remote; Spider monkeys were in the trees, turkeys roamed everywhere and we caught a picture of a strange rodent we couldn’t identify foraging in a clearing. We wandered through areas with names like “The Lost World” and took some pictures for Luis and Lacey from Lost World Expedition before coming around a corner and seeing Templo V.

Until recent years, Templo V had been overgrown and covered with dirt. Excavation and restoration has revealed a tall, steep pyramid that took its place as one of our favorites. Walking around to its far side, we saw another wooden staircase, this one even steeper and maybe twice as tall as the other. Queasily, we started to climb. And climb. And climb, hands sweating on the polished wood railings and trying not to notice the sections that were newer, implying that they’d been replaced recently after having been pried loose by the death grip of a terrified tourist. About 200 feet above, we stepped off the stairs and onto a narrow ledge leading across the top of the pyramid in front of a temple building. I’ve done a fair amount of rock climbing and am no stranger to heights, but this exposure set my stomach to turning, possibly because I couldn’t shake the image of 25 people at a time clambering around up here during peak hours. Backs to the wall, we took in ruins peeking through the canopy and jungle extending in all directions for as far as could see (between closing our eyes to make the spinning stop). We carefully backed down the 200 or so steps, slowly lowering ourselves and confirming our footing, amazed at the fact that they let people climb them.

As the truck came into view where we’d parked it in the lot in front of the ruins, Ann stopped and let out a sigh. She’d left her water bottle, a favorite aluminum one handed out after our first (and only) Olympic distance triathlon, under the “stairs of death” at Templo V. The sun was still up but starting to filter through the trees, beams flaring into stars as the leaves fluttered, and it would be getting dark along the overgrown paths. Gallantly, I quickly stated that there was no way I was going to walk 25 minutes back to get it; I was beat after the border and our late afternoon push to see the ruin. But Ann said she had the energy and set off back up the path, disappearing in the distance.

10 minutes later she was coming towards me at a trot, no water bottle in hand. After hearing a rustle in the bushes on the first section of path, two coatimundi had emerged and crossed in front of her. That was no problem; They’re pretty cute. When the other 15 followed across her path, apparently on their way to a particularly popular ant hill, she’d gotten a little more unnerved. At the top of the first set of stairs, there’s an open area. Here she’d started imagining jaguars watching her from behind every thin tree, rotating their slender bodies like the hands on a clock to conceal their presence, and decided to turn back. Putting what was left of the training that had earned her the Marin Triathlon water bottle in the first place to work, she’d made time back to the car.

That night, we emailed Tree and Stevie from SprinterLife who were a couple days behind us, having been shamelessly stealing our best ideas for months, and gave them specific instructions on where they could find the water bottle when they visited Tikal. But in the morning, we gave it one more try and did a brisk walk back up to Templo V. By 10am, the bottle was gone; I like to picture a coatimundi using it to wash down a mouthful of ants.

There’s not much on the road between Tikal and Rio Dulce, an inlet on the Caribbean Sea just below Belize, except fincas, gas stations and small towns that feel a bit more like Asia than Central America; Trucks and carts were piled high with products for the market, crowds gathered along the side of the streets and “chicken buses” – retired US school busses painted in bright colors and decorated with sparkles and tassels which uniquely identify them to a largely illiterate population for whom destination signs would be useless – belched smoke as they lumbered along with every seat (including the roof rack) filled.

We saw signs for Hacienda Tijax, recommended by James and Angela, just before the bridge that crosses the Rio Dulce and bumped along a dirt road through lush, tropical ranchland to reach the parking area. It took a second to notice the walkway, a series of suspension bridges a few feet above the ground, that extended from the back of the lot 300 feet into the jungle before disappearing. Just as the rain started, we bounced along the bridges as they slung across waterways and over soggy wetlands, catching glimpses of cabanas built on stilts between the trees. We emerged to find a pool and open-air, riverfront restaurant and booked one of the cabanas we’d seen.

We spent the next two days eating carne al pimiento (pepper steak) with french fries, drinking Gallo beer and discussing the layouts and amenities of luxury boats in back issues of “Yachting” magazine as the rain fell on the corrugated steel roof above us and the river flowed by in front.