A “Banana Republic” is a state installed largely for the benefit of a tight group of, usually foreign, corporations. The tropical climate along the northern coast of Honduras is perfect for banana plantations, and in the early 1900’s, American companies bought up huge amounts of land and developed railroads to bring the fruit to port for shipment to the US. To protect these investments, Honduras became the model of the Banana Republic. How that lead to selling skinny jeans and playing infuriating remixes of Christmas songs at deafening volumes from Halloween to Valentine’s Day is anybody’s guess.

Before this trip, I tended to think of all Central American countries as dense jungles of bananas and palm trees. In fact, the region of northern El Salvador and the western highlands of Honduras at times look more like the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in California. Unfortunately, unchecked logging and clearing for livestock has decimated much of the forest.

After crossing into Honduras at El Poy, our caravan had been hoping to reach the Mayan ruin site at Copan. We’d been told it was about 3 hours from the border, but as soon as we saw the condition of the roads, all estimates went out the window. Huge potholes a foot deep pocked the pavement, threatening to swallow up an entire wheel. Rippling “hundimientos” were linear sink holes that looked like the road had melted and slipped a few feet in either direction and required careful navigation of the resulting gully of strained roadway. And at times, the pavement disappeared altogether, either finally becoming more pothole than road or having been stripped away during a repair project that may or may not still be underway. When the sky opened up with a torrent of thick rain, we just had to laugh; Welcome to Honduras.

After not too long, we came to our first police checkpoint, and all three vehicles were flagged over. “Here we go,” Ann said from the passenger seat. I wasn’t ready to assume the worst yet and greeted the officer, dressed in the all black Honduran police uniform with tall leather boots and a short-brimmed cap that have a distinctly military feel, in Spanish as he approached my window. He shook my hand and flashed a toothy grin, two things common to all stories I’ve heard about police shakedowns.

It’s a bit of an ongoing debate as to whether an actual law exists, but a prepared overlander knows that Honduran police officers will ask gringos if they have orange safety triangles and/or a fire extinguisher. When an unsuspecting target says “I need to have a what?” there’s a song and dance about a fine that has to be paid at the police station many miles away which leads to the generous offer from the officer to personally accept a smaller fine on the spot. Not only did we have safety triangles and a fire extinguisher, we were prepared to convincingly agree to pay any fine at the police station, thus calling the bluff and making it not worth the cop’s effort.

But after requesting our passports, this cop asked us a question in Spanish that we didn’t immediately understand. Through some miming and pointing up at a nearby streetlight, we figured out that he was asking if we had a flashlight and assumed this was the latest evolution of the triangle scam. I reached down beside my left leg and grabbed the large rechargeable Maglite mounted in a charging cradle on the door to show to him.

“Necesito un roko,” he said, eyes lighting up at the long, black cylindrical metal body of the Maglite that is pretty much the standard issue for law enforcement in the US. Our new vocab word for the day was “roko,” a flashlight.

I held it up again. Yes, I understand that we need to have a flashlight and here it is.

“Necessito un roko,” he tried again.

Wait, did he say “necessita” or “necessito” that time? Is he saying we need a flashlight or he needs one?

All doubt faded when he said “Regalemelo?” (Will you give it to me?)

In that instant, we apparently stopped understanding all Spanish and began responding to everything he said with an apologetic “No entiendo” (I don’t understand) and a shoulder shrug. He looked back and forth between us, searching for a glimmer of comprehension as he repeated his request a few times and got only an alternating chorus of “No entiendo” back. I thought I blew it when he asked in Spanish if we had a pen; Without thinking, I turned, opened the center console and got one for him. He didn’t seem to notice my momentary language recovery and instead, wrote very carefully on his hand, “Yo necessito un roko.” We looked at him like he’d written in Chinese. He smiled a “You can’t blame a guy for trying” smile and waved us on. I’d decided not to expect the worst from Honduran cops, but the next one who comes to the window will be greeted with a big ol’ “Howdy, pardner! Y’all sure do talk funny in these here parts.”

With our progress a little slower than planned and a lengthy border crossing, we adjusted our goal from the charming, cobbled town of Copan Ruinas, just outside the archeological site, to the busy, dirty crossroads of Santa Rosa de Copan a couple hours short. Leading our caravan of various sizes through the tight streets of the old town, we pulled into the first hotel we found with a large, fenced lot. Despite dark, cramped rooms with paper thin walls and twin size fitted sheets on full beds, we managed to make ourselves at home.

From the heads turning in the central square, I’m guessing Santa Rosa de Copan doesn’t get much gringo traffic, though they were most interested in the two dogs on leashes. Dogs, as pets! Imagine! A few local kids cautiously approached Kiki, more teddy bear than dog, asking “Muerde?” The verb for “bite” and “kill” are only one letter apart, so I always think kids are asking “Does your dog kill?”

Tree and Tree and Stevie

Emily with Luna

You can pet dogs???

The town of Copan Ruinas, just across the border from Guatemala, is a popular day trip Antigua. Despite tons of hotels, hostels and restaurants catering to tourists, it was actually quite a cool little town. Soon after crossing the narrow bridge into town, a tuk-tuk driver attached himself to us and insisted on leading us around to a few hotels. With parking for the Sprinter a primary concern, we accepted his help and settled in at a nice, 10 room hotel surrounding a pool on the top of a hill overlooking the town. We also arranged our helper to bring us back to the ruins a little later in the day. With a set rate of $2 per person, I’m still unclear on why we all decided to squeeze into the back seat of a single tuk-tuk.

Ann felt particularly safe at the entrance gate with her friend, the 15 year-old kid with a huge gun.

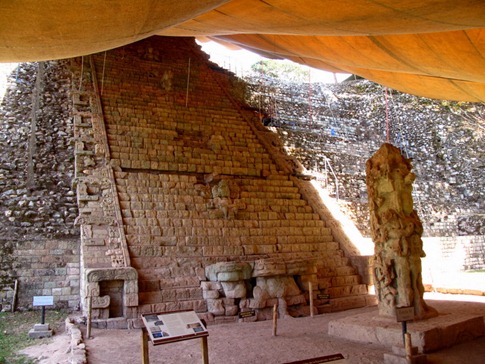

The ruins at Copan are more known for their intricate stone carvings than the size of the city or scale of the ruins. While we’ll admit to being a bit “ruin saturated,” the tightly-packed site, much of it still only peaking from the hillsides into which it was built and subject to the whims of the massive roots of the huge Ceiba trees that grow all around it, had something of an “Indiana Jones” feel as we chose our own paths up and down the huge stone stairways.

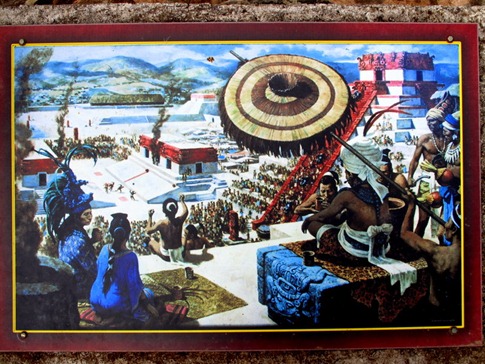

The stonework, from carved decorative features to expressive, oversized heads, is the main attractions of the site. This “Hieroglyphic Staircase” can be seen in an artist’s rendering below.

But the massive Ceiba trees with branches at least 4 feet in diameter coming off huge trunks and the wide roots finning out to support it all were just as interesting.

it’s amazing the places they’ll let you go in these ruins.

This little bug had created a camouflaged crust of sand and thought he was invisible even on this railing.

Five or six Scarlett Macaws roamed around near the entrance.

From Copan, we’ll continue north on the main road towards San Pedro Sula before cutting down to Lago de Yojua. From there, the Nicaragua border should be a 5 hour drive through Tegucigalpa, and we’ll know whether our detour through Honduras has paid off.